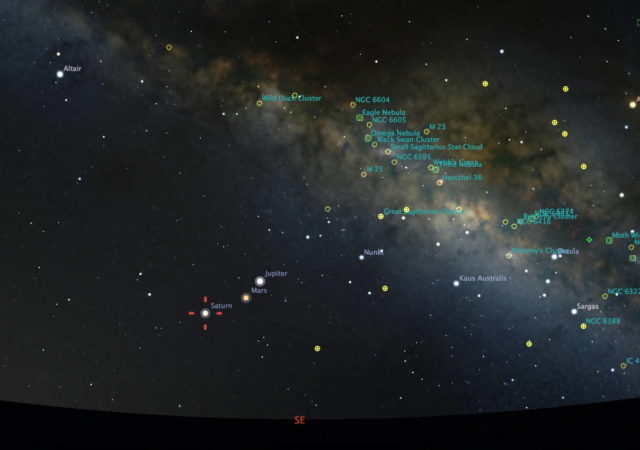

For several weeks the planets Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn have been visible in the same portion of the morning sky. These are all bright and easily visible even during twilight hours. Nestled in between these bright planets lies the minor planet Pluto.

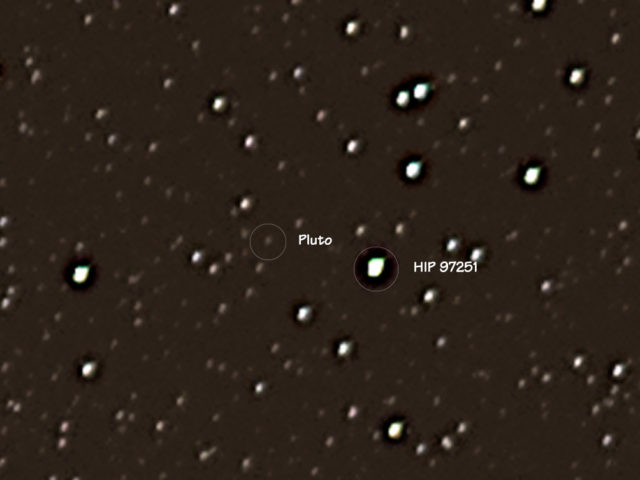

So I thought it would be interesting to photograph Pluto. Pluto is much too faint (currently Mag. 14.3) for me to find with my camera/lens setup. However, Pluto and Mars passed very close to each other (~10 arc minutes, or less than the diameter of the Moon) on 23 March 2020 making it easier to find one based on the location of the other. Clouds forced me to shoot this image a day later on 24 March 2020, when they were farther apart.

I used Stellarium as a guide to hopping from one star to another—comparing the photographs with Stellarium star charts—until I finally located Pluto. As a magnitude 14.3 object, this was near the limit of what could be resolved with my Nikon 180mm AI-s f/2.8 lens shot wide open.

Images were shot at f/2.8, ISO 1600, and 30s. The best images were stacked to reduce noise. Post processing included large values of Unsharpen Mask to help sharpen the dimmest stars and Pluto—with the undesired side effect of creating halos around the brighter stars.

Check the video to see how much Mars moves in just 15 minutes.

I was able to capture four planets in the morning sky. In the previous post, I was able to capture four planets in the evening sky. It was a challenging project that I wanted to do and have now completed.

Maybe I should get a telescope.

Oh, one final point. Once again I was photo-bombed by a cluster of Starlink satellites. Sadly, the day is coming soon when night photography will be very difficult because of these satellites.